Sex & Power, Gender &Transgression: LGBT+ Diversity in the 15th and 16th Centuries

Sex and Power, Gender and Transgression: Lessons for Today from LGBT+ Diversity in the 15th and 16th Centuries

April 12, 2023

Good afternoon, my name is Rebecca Stevenson. It is a pleasure to be here, speaking about Sexuality, Gender, Power, and Queerness in the 15th and 16th century World.

Cut Sleeves and Bitten Peaches

Is it possible to understand the inner worlds of people we’d call LGBT+ from 600 years ago? Or to understand how they defined themselves, how they accessed or lost social power? Or how social systems shaped the meaning of sexual and gender behavior?

Stories and poetry are decoder rings for queer interiorities of the past. Writings from queer points of view allow for self-definition in context, and reveal eddies of social power and transgression. And stories illuminate the rainbow palate of diverse sexualities, identities, intimacies and genders now.

Today we’re going on a round-the-world 15th and 16th century forage for just a few of the many many recorded queer stories. We’ll start in China:

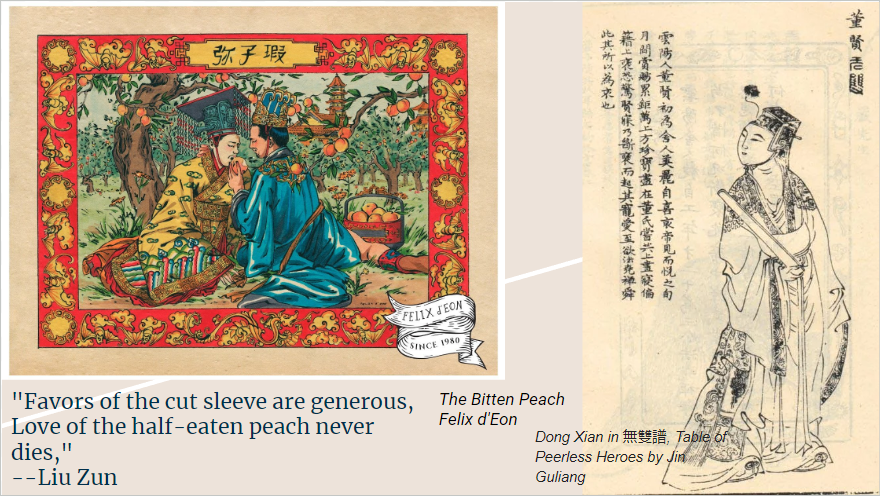

"Favors of the cut sleeve are generous,/ Love of the half-eaten peach never dies,"

--Liu Zun

When men in Ming dynasty China, (14th, 15th and 16th centuries ) referred to their same-sex romantic relationships, they invoked the imagery of the Cut Sleeve and Bitten Peach, which tied them to the tradition of Courtly homosexuality originating in the Imperial past.

First, The Passion of The Cut Sleeve, 斷袖之癖 --Duàn xiù zhī pǐ

The young Emperor Ai (25 BC) had a favored companion, a man named Dǒng xián 董賢. The Emperor showered position and favors on his friend, building him a grand palace, making him a general, and even naming him his heir.

One afternoon, the pair dozed together. The emperor woke to attend to his work, but as he sat up, he saw his long sleeve was caught beneath the other man’s body. He didn’t want to disturb his companion, so he reached to their pile of discarded clothes, retrieved his sword, and cut the fine embroidered silk of his own sleeve, letting it fall to the mat to remain under his sleeping lover. The emperor appeared with his sleeve cut off before his ministers, and The Passion of the Cut sleeve came to denote a particularly Han Chinese tradition of same-sex devotion and love.

In 14th,15th and 16th century China, increased literacy and printing technology, Cutlseeve and bitten peach stories by such popular writers as The Moon Heart Master of the Drunken West Lake and his commentator, I kid you not, The Daoist Master Haha What Can You Do About Fate (奈何天呵呵道人) spread these stories.

And the bitten peach?

The Half-Eaten Peach (recorded in Han Fei Zi by Han Fei)

In Zhou dynasty China, Mizi Xia was a courtesan irresistible to women and men alike. Duke Ling of Wei doted on him.

One day, the two men walked through the peach orchards. Lovely Mizi Xia picked a peach and tasted it. He exclaimed it was the sweetest thing he had ever eaten, and insisted his Duke try it. The Duke accepted the half-bitten peach from Mizi Xia’s own hand. It was sweet. The two men, Duke and beloved companion, were happy together for a time.

But one day, Mizi Xia received terrible news-- his mother was ill. Forging the Duke’s signature, he stole the Duke’s carriage to rush to her side.

He knew the punishment he deserved: thieves were to have both feet cut off.

But the Duke forgave him, and praised his filial piety.

Years passed and the lovely Mizi Xia grew older. Like a plucked blossom, he lost his looks. The once besotted Duke cooled to him. Even the memory of the sweet peach, once a symbol of their close affection, soured. How dare a mere courtesan offer a Duke food from his mouth? Reminded of the stolen carriage, the Duke punished Mizi Xia retroactively, all sweetness between them turned to bitterness.

This story is a romance and a warning.

When recording this story in his treatise on Confucian philosophy, Han Fei said,“If you gain the ruler’s love, your wisdom will be appreciated and you will enjoy his favor as well; but if he hates you, not only will your wisdom be rejected, but you will be regarded as a criminal and thrust aside” (Hinsch 21, quoting the Han Fei Zi).

If your access to freedom and privilege is from a love affair with a powerful man, get out before your looks go!

When men in Ming China alluded to these stories to reference their own sexual relationships, they tied themselves to the ancient Chinese elite during a time when homosexuality was more associated with brothels and foreigners. It elevated ancient ethnic-Han queerness in a context where the new ethnic-Yuan ruling dynasty was eager to distance itself from the scholarly effeminacy of past rulers. Cutsleeve is both a celebratory and derogatory term, as so many words are when we venture into conversations about queerness.

(Hinsch 1992, p119) “The Ming was a time of intense awareness of the long tradition that had accrued to male love at that time. The reading public was dramatically increasing thanks to a population explosion, growing literacy, and refintemenst in printing technology. These new readers could look back on almost 2000 years of written accounts concerning the cut sleeve.”

Hinsch 1992, 120: “The long past that accrued to the shared peach gave later imperial homosexuality an increasing air of self-awareness and tradition. Men of Ming Beijing and Suzhou could proudly point to the remote antiquity of the Shou and Han as a righteous model for their own sexual practices.” Hinsch 24: “Zhuang Xin did not see his plight in temporal isolation; instead he drew on a homosexual tradition that could comfort him by allowing him to place his situation in a broader social and historical context, and used as a past example to justify his present actions.”

Status and risk are braided to minority sexualities, whether they are understood as behaviors or identities. There were precarious privileges under that queer umbrella, and punishments for veering from gender norms, as we see from this and other queer stories from around the Renaissance-era world.

I’m coming at this quest with several lenses: I’m a folklorist, and so I take stories seriously. Stories organize meaning out of cultural randomness, like dragging a fleece through a carding comb. You won’t change what’s there, but you get all the strands in an order. The strands in story are meaning, context, and empathy.

I’m an educator with a background in indigenous language education, so I’m interested in how meaning is constructed through language outside of the white Western frame of reference. Emic and indigenous self-definition matters.

I am queer, so I am interested in stories that reflect, disguise, define, orbit, celebrate, elevate and interrogate queerness. And I’m a fan: an unapologetic enjoyer of things. I’m interested in how canonical works are creatively transformed by fan audiences.

Note: For those of you unfamiliar with the term fangirl, here’s a primer. Fandom is when people really REALLY like stuff. Sherlockians play The Great Game. Shakespeareans rebuild The Globe. Often fandom is a place where people get really expertly invested in source material and create community around it, gathering for, say, centenary celebrations, to meet with like-minded souls and bond over beloved works. Fandom is an interrogation of canon. Fans are, like historians, are very intense consumers of the source material, and even with the same fraction of, say, half-translated Sapphic verse, thirty fans (and/or historians) will arrive at thirty adamant and contradictory opinions. For years, while the Hayes code kept queer people, relationships, and behavior off of screens, fandom was a place to investigate (or possibly hallucinate) queer storylines in canonical media. Since Spock and Kirk, Watson and Holmes, queer fandom is an interesting training ground for sleuthing out SUBTEXT from the text. Queer fans turn their gaydar to a canon that does not explicitly include them, to analyze the heck out of it and rework it and reimagine it until it reflects the experiences that they want to see reflected in the works they love.

Language

So, a brief foray into the verbiage.

English terms for sexuality and gender don’t precisely match the concepts in other languages, times, and cultures. Without the native words for identities or behaviors, we lose complexity to translation. But we’ll forge on with the imperfect language that we’ve got.

Trying to define sexuality and gender precisely is like fighting with a curtain, like nailing aspic to the wall. It defies precision!

I use the term “Queer” which was a nasty pejorative for at least a century until its reclamation as a useful rainbow umbrella term.

The label LGBT+ stands for lesbian gay bisexual transgender, with many other identities included under that + sign: queer intersex asexual two spirit pansexual nonbinary agender, and others sexual orientations and genders.

(Note: The term “LGBT+” in English and LGBT cultural markers (like coming out or campaigning for legal same-sex marriage) arise from American usage, largely in the aftermath of the LGBT rights campaigns in the US, spurred by violence and discrimination and the need for a strong group identity to resist oppression, such as “gay panic” laws that allowed straight men to murder gay men and transgender women without legal recrimination. In order for there to be wide-spread support for legal reforms protecting LGBT people, LGBT people had to identify themselves. “We’re here, we’re queer!” You can’t ask for support for a group if there’s no evidence the group exists. Resistance requires words.)

Sexual orientation is who you want to sleep with, people who are the same as you, or different from you. And what is gender? Anywhere you cast your eye across the historical horizon, there is gender happening. Gender is defined by some combination of biological sex-characteristics, sexual behavior, reproduction, age, self-perception, status, spiritual calling, and social roles, each prioritized to different degrees depending on the social context. When we say gender is a construct, that’s what we mean. If we are counting just those variables, that allows for literally a million different combinations. Maybe it shouldn’t be a surprise that “normal” genders and “queer” genders are defined differently by time and place. Gender is changeable but it’s a big deal. It is likely to lead to either marginalization or power.

The term “homosexual” in English has been around since 1868 as “Homosexualität,” thanks to the gay journalist Karl-Maria Benkert. It came to mean a medicalized, often pathologized, type of human. Today, laboring under the 18th century legacy of taxonomical classification, identifying your own gender and sexual orientation is like following a botanical field guide. It’s a useful, if esoteric exercise. Do I have opposite leaves and a square stem? I must be mint! Do I have no internal sense of gender, and attraction to others regardless of gender? I must be agender, and pansexual!

In this way, through self-scrutiny, we pinpoint exactly the card deck of identity labels that best line up with who we discover ourselves born to be.

But even without a category like “homosexual” people have existed beyond the binary of male-female and have been in same-sex erotic and romantic relationships since always. The gay essentialist Norton (2016) even argues that there is a universal queer culture that transcends time and place! But the constructionist Schick tempers that claim: (2021) “same-sex relations were viewed in pre-modern times as merely a predilection or practice, whereas during the 19th century they came to be considered an innate nature, an identity.”

This is an often repeated view, that there was no concept of “a homosexual person” in the past, but this is only true if you ignore queer self-definition outside of the Northern European elite. I’ve already mentioned “cut-sleeve”, a 2000 year old term that’s still going strong. I’ve stumbled across other early gay identities such as “onna-girai” woman-haters from medieval Japan, female Tribads--, and mahu from Hawaii are just a few terms of queer self-definition. Even Medieval European texts talk about “born Eunuchs.” “Sodomite” was a category of person in Renaissance England, as was Ingle, and Uranians and Mollies later on.

(Note: Norton's critique of social constructionism: The term sodomite predates the verb sodomy! Florio in an English-Italian dictionary of 1598 cites the following: Sodomia, the naturall sin of Sodomie. Sodomita, a sodomite, a buggrer. Sodomitare, to commit the sinne of Sodomie, Sodomitarie, sodomiticall tricks. Sodomitico, sodomiticall Florio uses 'Sodometrie' as an English word. Thomas Nashe referred to ‘the art of sodomitry’ in 1594.)

Norton: In England the ingle, a word documented from 1532 in a translation of Rabelais, occurring more frequently from the 1590s, was a catamite, or kept boy, from Latin inguen, groin. The 'ingle' formed part of a pair, for the keeper of such a boy was also given a separate term, the ingler, recorded from 1598.

So it’s not accurate to say there was NEVER such a thing as a queer category of person until the medicalization of homosexuality in the 19th century.

However, those past same-sex relationships and gender-bending behaviors DID have meanings in their historical contexts that we shouldn’t presume to grok just because of surface similarities. I am chumming choppy waters here, wading into the blood feud between essentialism (ARE you queer) and constructionism (DO you queer?)

(Note: “According to Foucault, sexuality is a great surface network in which the stimulation of bodies, the intensification of pleasures, the incitement to discourse, the formation of special knowledges, the strengthening of controls and resistances, are linked to one another, in accordance with a few major strategies of knowledge and power.'” Halberin 1989)

Note: Hirsch 8 Constructionists vs. essentialists: “These positions have been portrayed as opposites, with a resulting polarization of studies regarding homosexuality. As a partial remedy to this split we should recall that anthropologists such as Claude Levi-Strauss often note how human beings tend to divide the organic whole of reality into what sometimes seems like arbitrary polarities. Academic culture is not immune to this love of bifurcation. In fact, these “opposite” conceptions of homosexuality can be reconciled as simply different aspects of a complex phenomenon. The two groups disagree about the etiology of homosexuality because they see the phenomenon of homosexuality differently. Essentialists define homosexuality psychologically, according to inner thoughts, desires, and predispositions. Social constructionists prefer a behavior definition, viewing homosexuality primarily as an action. Essentialists therefore emphasize factors of biology or psychology that condition individual tendencies, while social constructionists concentrate on how society shapes the expression of individual sexuality. Rather than mutual contradiction, both points of view have heuristic value for the investigation of sexuality on the level both of individuals and of society as a whole.”

But we MUST have some cultural humility when we go looking for queer diversity in the past. Things MEANT different things that they mean now. Things meant different things BACK then, depending on whom you asked!

The historical meaning of sexuality is particularly, FORGIVE me, slippery.

Historical records of Homosexual Acts Vs. Queer Interiority

The writings that survive about historical sexuality are evocative but incomplete, and all of them charged with purpose. Someone had a reason for recording them. Money, or power, or as a warning, or as a seduction-- there is no neutral artifact of human sexuality.

Other history fans-- I mean historians-- have done thorough trawls through the historical canon for queer catches from the past, looking for recognizable evidence of people “doing gay stuff”. There’s plenty to find: pornography and explicit love letters, medical texts, art, graffiti, court records, diaries, sex manuals, jokes, poems, plays, contemporary accounts, lewd pottery, and religious prohibitions. People have been having gay sex for ever. So does that conclude the investigation? Was there LGBT+ diversity, look here’s porn, yes there was? No, that seems prurient and reductive. It ignores meaning. What about queer relationship? Power? Commitment? Is LGBT+ diversity about more than who sticks what where?

There are other artifacts that seem queer to modern readers but aren’t sexually explicit and so are dismissed by non-queer historians: commitment ceremonies between members of the same sex, odes to loyalty and the true bonds between chosen brothers, folktales, myths, ceremonies, poetry with ambiguous pronouns, religious texts that describe transcendence in terms of same-sex love.

(Note: Homophobic scholars have gone to great lengths to say, “none of this is gay!” But now we have the option of saying, well, maybe it is! Maybe there’s nothing wrong with the queerness in me recognizing itself in this ambiguous text. We can’t know it was gay, but we can’t know it was straight, either.)

While medical, legal, explorer and religious reports present the facts of historical homosexuality, poetry tells the internal story.

(Note: Norton interview: "I think a greater understanding of this identity can be achieved by a focus, for example, on the pleasures of the molly house and the camaraderie between men who loved one another, than upon the homophobic courtroom and statistics of hangings.")

Stories contextualize the meanings of gender and sexual diversity and have humanity that we can empathize with. To understand the tides of power and privilege, of native meanings of LGBT+ diversity, the study of history can be cross-pollinated with such queer and maligned fields as folklore and fan studies.

(Note: Good old Rictor Norton: "Try not to become depressed! Constantly bear in mind that homophobia and homosexuality are two different things. Think about what exactly will be your field of research. If you start off concentrating on attitudes towards homosexuality, you’ll be drawn into focusing on legal definitions and works by zealous Christians and psychiatrists – and the catalogue of views you assemble will be pretty depressing! Try to avoid writing a history of victims and martyrs: a catalogue of executions may achieve little more than feelings of resentment. Remember that the opinions of society are largely homophobic, and law and religion are even more homophobic because they change so slowly and seldom keep up with the times. Narrow in upon your real subjects, which are lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender individuals, perhaps by reading between the lines, so as to capture what their own feelings and relations were. In records of trials or sensational newspaper reports, give more weight to those precious moments when we hear the actual words of LGBTQ individuals. Try to tell the stories of what these individuals did and felt before that moment when they found themselves in court, focusing on their relations with one another and with family and friends.")

15th and 16th c World Stories

Folkloristic studies of tale-types show that stories travel, like genes, across every border. The queer renaissance world was an interconnected one. Gary Leupp (1995, 12) says, “many societies regarded the male-male sexuality in their own midst as a foreign import… The ancient Hebrews associated (it) with the pagan Egyptian and Canaanite cultures, the ancient Greeks believed they had “learned” pederasty from the Persians; medieval Europeans regarded sodomy as an Arab peccadillo introduced into their culture by returning Crusaders. Many English of the Renaissance were convinced that the “unmentionable vice” of sodomy had reached their lands from abroad; depending upon the state of their international relations, they blamed Castile, Italy, Turkey, or France.” Japan credited China, and later China blamed Japan. Queerness and outsider status are linked.

Clearly there was a lot of... cultural intercourse.

For the sake of time, all I’ll say about Northern Europe is that they revered intimate homosocial bonds, and had a horror of anal sex. In 16th century England, sexuality in general was suspect as a distraction from religious devotion, and sodomy in particular, whether with man, woman, or beast. With An Acte for the punishment of the vice of Buggerie , Henry 8th in 1533 made sure that sodomy was punished (all proceeds going to the crown), setting a money-making precedent that would last until 1835, adding financial incentive to the persecution of suspected “sodomites.” Renowned folklorist Alan Dundes tittered that there was a Northern horror of “anality.” “"No other people had looked upon this act (of sodomy) with so much disgust or judged those participating in it as harshly" (Quoted in Dundes 2002) as the English. However, Renaissance England elevated homosocial intimate relationships, so long as they excluded anal sex, such as the intense and loving same-sex bonds of the monastery, the school, or the battlefield. Today we’d consolidate these relationships: if the love of your life is of the same sex as you, you’re queer. If you’re having sex with them, you’re queer. England wanted to keep those separate. The ambivalence towards queer masculinity is palpable in Renaissance England.

(Note: Bray says “Two images… exercised a compelling grip on the imagination of sixteenth-century England, if the many references to them are a reliable guide to its dreams and fears. One is the image of the masculine friend. The other is the figure called the sodomite. The reaction these two images prompted was wildly different; the one was universally admired, the other execrated and feared: and yet in their uncompromising symmetry they paralleled each other in an uncanny way.”)

While I’m blithing getting in over my head with old academic blood-fueds, here’s Shakespeare! Our boy Shakespeare wrote this sonnet which praises a fair youth as a perfect physical specimen, with every attractive trait a woman has, but without any nasty femaleness. He laments that god added only one (eh-hem) extra Thing to his perfect beauty, making him for women to love, and not for the speaker himself. SONNET XX " A woman's face, with Nature's own hand painted, Hast thou, the master-mistress of my passion; A woman's gentle heart, but not acquainted With shifting change, as is false women's fashion; An eye more bright than theirs, less false in rolling, Gilding the object whereupon it gazeth; A man in hue, all hues in his controlling, Which steals men's eyes, and women's souls amazeth; And for a woman wert thou first created; Till Nature, as she wrought thee, fell a-doting, And by addition me of thee defeated, By adding one thing to my purpose nothing. But since she pricked thee out for women's pleasure, Mine be thy love, and thy love's use their treasure

FLORENCE: Plato and God

Further south, in Florence, enormous wealth and power crashed across Europe in great tidal surges. Religion met and mingled with mathematics, producing brainchildren with hybrid vigor: neoclassicism and catholicism; platonic ideals and Christian aspirations. As a worldy urban center, Florence was known as a place where men loved men. There was tension between the neo-classical celebration of homosexuality and the Christian prohibitions against base sensuality in general and sodomy in particular.

Patriarchal societies in the Renaissance protected a gender binary of 0s and 1s: the presence or absence of a phallus. There is the Man (the one who utilizes a Phallus) and the not-man, the one who, um, takes the phallus.We may call this a phallic fallacy. It meant that men could sleep with other males without compromising their gender or breaking religious taboos against sodomy, as long as they only admitted to being the “top.” Men who admitted to being sodomized were punished with fines, or in a small percentage of cases banishment or death.

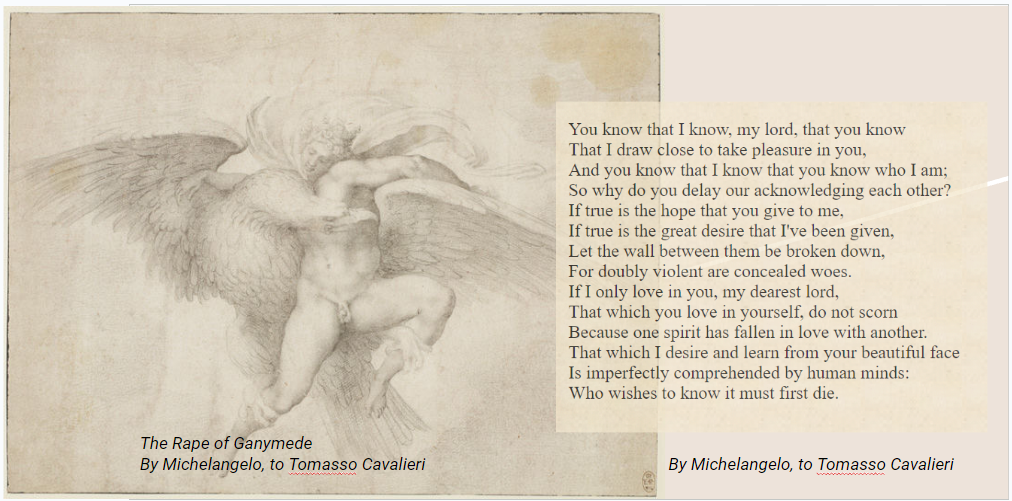

Florentine masters created enduring odes to same-sex love and the perfection of the male form.

Michelangelo’s “conception of Love was close along the line of Plato's. For him the body was the symbol, the expression, the dwelling place of some divine beauty.” (Carpenter 1908)

Michelangelo pursued that divine beauty as he found it in the form of a younger man, of higher birth than himself, named Tommaso de' Cavalieri. He sent letters, poems and unsolicited homoerotic pics. He wrote:

You know that I know, my lord, that you know

That I draw close to take pleasure in you,

And you know that I know that you know who I am;

So why do you delay our acknowledging each other?

If true is the hope that you give to me,

If true is the great desire that I've been given,

Let the wall between them be broken down,

For doubly violent are concealed woes.

If I only love in you, my dearest lord,

That which you love in yourself, do not scorn

Because one spirit has fallen in love with another.

That which I desire and learn from your beautiful face

Is imperfectly comprehended by human minds:

Who wishes to know it must first die.

His physical love is spiritual; sanctified by its great potential to reveal divine truth.

And those racy pics? Michelangelo’s drawings to Tommaso included the Rape of Ganymede and The Punishment of Tityos, images with luscious male bodies entwined in a discord of muscular eagle wings. In the first is rapture and elevation, as the boy Ganymede is taken by Jove in the form of an eagle, in the second is ravishment and destruction, as Tityos is devoured by an Eagle. Same-sex desire had the ability to elevate and to desecrate-- to fly and to crush.

“In a revealing episode, Cardinal Ippolito de' Medici came to visit and asked to borrow the drawings so he could have them copied, and Tommaso tried to prevent that, but failed. He wrote to Michelangelo, "I did my best to save the Ganymede," which suggests that of all the drawings, they're aware that the Ganymede most expresses sensitive or scandalous relations between them.” (Saslow)

The public exposure was risky for the young aristocrat. (Fraiman 2018.) Male-male intimacy was commonly tolerated, as long as the details remained private, and as long as the sensibilities of masculine gender were not violated. Desiring beautiful youths was seen as natural for any red-blooded adult man. Allowing yourself to become known as a receptive partner to those attentions? That was unmanly and could damage one’s reputation and risk one’s freedom if discovered.

As he aged, Michaelangelo devoted his energy to attaining spiritual rather than physical transcendence, turning his eyes to God. Michael Angelo’s religious fervor and his homoerotic fever burned with matched intensity.

In the mountains of Spain, there was a religious mystic who wrote decidedly queer poetry about his spiritual union with Christ.

St John of the Cross was a Spanish Carmelite Friar, born in 1542. He drew inspiration from earlier poets’ mystic homoerotic poetry in Hebrew and Persian.

(note: "Samuel Ibn Nagrillah (993-1056) was one of the most creative and prolific of the Hebrew poets of Spain Lovely gazelle, heaven-sent blessing on earth,"1' remove me from the snare.(2) Satiate me with beneficence 3) from your tongue, like a jar 4) filled with good wine. What advantage have you that you crush hearts, with shining face and dark hair, And roving"5) eye, black as night, on ruddy cheek? 5 How do you ply your craft upon the feelings and hearts - without knowing craft?(6) You prevail over heroes, and not with weapons, and over swords, without an army. You cure the mortally wounded without medicine or any healing on the wound. Tell me, is there an end to your roaming, and how long? How, oh how Can you stand among friends and shoot them with your arrows and bent bow? 10 And how can you choose death for the righteous, when their life or death is in your hands? You exult in their ills like an enemy - why does one like you do so? 48 (Roth 1982))

“The image in the poem ‘On A Dark Night’ is of becoming one with Christ in the experience of making love with a strange man in a park late at night–and waking to find they are lying in a field of lilies” (Johnson 2000).

1. One dark night,

fired with love’s urgent longings

– ah, the sheer grace! –

I went out unseen,

In darkness, and secure,

by the secret ladder, disguised,

my house being now all stilled.

3. On that glad night,

in secret, for no one saw me,

nor did I look at anything,

with no other light or guide

than the one that burned in my heart.

4. This guided me

more surely than the light of noon

to where he was awaiting me

– him I knew so well –

there in a place where no one appeared.

5. O guiding night!

O night more lovely than the dawn!

O night that has united

the Lover with his beloved,

transforming the beloved in his Lover.

6. Upon my flowering breast

which I kept wholly for him alone,

there he lay sleeping,

and I caressing him

there in a breeze from the fanning cedars.

7. When the breeze blew from the turret,

as I parted his hair,

it wounded my neck

with its gentle hand,

suspending all my senses.

8. I abandoned and forgot myself,

laying my face on my Beloved;

all things ceased; I went out from myself,

leaving my cares

forgotten among the lilies.

Queer imagination was a pathway to the divine.

(Note: pleasure and transcendence, like this one by the Sufi poet Rumi, who wrote about his union with his master/teacher/love Shams. Does he speak of Shams or God or the self? It is the same. (Rumi 2006)

OTTOMAN: Adore the Beloved, and Beware Pride

Next to the Ottoman empire at its nadir.

(In the Ottoman Empire, the “beloved boy” in a male-male romantic relationship could be (Shamgunova 2022) “anywhere between prepubescent age and his late 20s; he could be bearded or unbearded, muscular or androgynous, free or enslaved. However, in the vast majority of cases, he would be in the socially inferior position to the uşşak ‘lover’ in some form – as a slave, servant or, in the case of sultan’s relationships with other men, subject.” Power was lopsided. This power dynamic is alien to the egalitarian ideals of today’s relationships, both hetero and homosexual. Today, we expect and deserve to be on equal footing with our partners. Schick (2018) explains that in Muslim countries, the strict segregation of men and women for the sake of women’s purity, made sex and affection between adult men (phallic) and beautiful boys (non-phallic) more acceptable than the risk of defiling someone else’s woman. The binary genders/sexualities of penetrator to penetrate were not static: age and social position defined gender: non-phallic boys can grow up and become phallic men (Murray 2007). But how the admirers grieved the moment when their lovers turned from acceptable objects of desire to unacceptable! Here are some poems about boys’ first beards. These outward signs mean that the boy is not an appropriate candidate for his admirer’s ardours. (Roth 1982) "With the nascent down the beauty of this boy was thinned, and our hearts also were made thin, of love of him. It is not that the blackness has covered his cheek, but that it has thereby discolored his black eyes!" "You were the full moon, until one night you were infected by decay. When the down sprouted, I said: "Love is finished. The black raven of down has announced separation!" Poor A-Xia of the bitten peach would understand how the boys felt.)

Queer romantic and erotic entanglements could be a pathway to soft power. Once the relationship ended, though… well. Soft power does not promise a soft landing.

Ibrahim was born in 1494 to a Greek father, a humble fisherman. But early in his childhood he was taken by corsairs as part of the tribute of Christian children, made a Eunuch, and sold as a slave. (Hester Jenkin’s description of what happened to him may sound familiar: “This tribute of Christian children had been levied since the reign of Orkhan (1326–1361) and was the material of which the redoubtable army of janissaries was formed. These children, separated from their own countries and their families, and practically always converted to Islam, were for the most part trained in military camps and forbidden to marry. Therefore they had no interest except in war, and no loyalty except to the sultan. Thus they developed into the finest military machine the world had known, the most perfect instrument for a conqueror’s use, but a dangerous force in time of peace.)

Ibrahim came into the service of Prince Suleiman, and the two became inseparable. They slept together in the prince’s apartments, bathed and ate together, rowed around in little boats together, and ran the mutes back and forth at all hours passing notes. Suleiman bought two of every fine piece of clothing he owned -- one for himself and one for Ibrahim.

In 1520, Suleiman became sultan and appointed Ibrahim to positions of increasing power, starting with head falconer, then master of the household, then Vizir, then Grand Vizir --general in chief of the Imperial forces.

Suleiman never denied Ibrahim anything, he was “dominated by his love for Ibrahim, and unable to resist any of his caprices” (Jenkins 1911) and gradually he gave over more and more of the business of his government to Ibrahim.

The Sultan himself wrote of Ibrahim: “All my victorious army, all my slaves, high or low, my functionaries and employees, the people of my kingdom, my provinces, the citizens and the peasants, the rich and the poor-- in short all shall recognize the above‐mentioned grand vizir as serasker, and shall esteem and venerate him in this capacity, regarding all that he says or believes as an order proceeding from my mouth which rains pearls.”

Ibrahim described his own power thus: “The mighty Sultan of the Turks has given to me, Ibrahim, all power and authority. It is I alone who do everything….To make war or conclude peace is in my hands, and I can distribute all treasure. My master’s kingdoms, lands, treasure, are confided to me.”

For thirteen years, Ibrahim was the highest ranking governor in the Ottoman empire. But his detractors mistrusted Ibrahim for his indulgence of Christian subjects and over-familiarity with the Sultan. There were rumors the Sultan was bewitched. And Ibrahim had powerful enemies: notably, Roxelana, Suleiman’s wife

When Ibrahim Pasha overstepped himself, and forgot that he was in fact a slave to the sultan, his fall was fast and hard. He told the Christian ambassadors from the Emperor Charles V that, “The fiercest of animals, the lion, must be conquered not by force, but by cleverness… I, Ibrahim Pasha, control my master, the Sultan of the Turks, with the stick of truth and justice. Charles’ ambassador should also control him in the same way.” (Jenkins 1911)

This was too far.

Jenkin’s account: On March 5th, 1533 Ibrahim Pasha betook himself to the imperial palace in Stamboul to dine with the sultan and spend the night with his Majesty, according to a long established custom. In the morning his body was found with marks on it, showing that he had been strangled after a fierce struggle. A horse with black trappings carried the dishonored body home and it was immediately buried in a dervish monastery in Galata, with no monument to mark its resting place. His immense property fell to the crown and Ibrahim Pasha, the mighty grand vizir, was dropped out of mind and conversation as though he had not practically ruled the empire for thirteen years. (Jenkins 1911)

The bond between sultan and subject, friends and lovers, master and slave had spanned the highest pinnacle of power and the deepest troughs of betrayal.

JAPAN: Boys are beautiful. Beauty is fleeting. Love is pain, turn to Buddha.

Islam, Judaism, and Christianity all nominally condemned sodomy while variously allowing for the homosocial, neoplatonic or master-servant bonds of same-sex intimacy.

Shinto, Buddhism,Taoism and Confucianism had no such explicit anti-sodomy bias. (Hirsch 31: From Intrigues of the Warring States (Zhang ce): “A beautiful lad can ruin an older head; a beautiful woman can tangle a tongue.”... “Sex in general is cautioned against as a disruptive force.”) Southern China recognized 兔儿神; Tùrshén, the Rabbit god of Homosexuality. Daoists thought male-male sex was less spiritually dangerous than male-female coupling, where female Yin could sap male Yang’s vitality. Yang-Yang dual cultivation could even lead to forming a greater spiritual core!

(Note on Rabbit God: (Hinsch 1992, p133): Tuer Shen backstory: set in Fujian. A solder falls for an official, spies on him, is caught and confesses, and is killed. He comes back as a rabbit spirit “and demands that the local men build a temple to him and burn incense in worship. The story concludes with the building of the temple: ‘According to the costumes of Fujian province, it is acceptable for a man and a boy to form a bond (qi) and to speak to each other as if to brothers.” They built the temple, made sacrifices. “This anecdote hints that the development of homosexual life in Ming Fujian might have been more highly developed than even the institution of male marriage would indicate. Not only did men form couples, but the male community a large seems to have been involved in organized homosexual cultic activity. Large-scale retirement parties, the all-male festival in Li Yu’s tale, and the development of religious rites centered around a cult of male homosecualty all point to involvement of the male community at large.”)

By the Muromachi period in Japan, (14-16th centuries) Buddhist monks had normalized, samurai formalized and merchants commercialized wakashudo-- the “dao” of loving male beauty. In the Edo period, the practice exploded to ubiquity as urban growth allowed a wealthy middle class to grow, and access the luxuries of the “Floating World.”.

Among the Samurai, it wasn’t just tolerance for a sexual predilection. It was a formal relationship between older and younger men, following the Confucian ideal of generational filial piety. The nanshoku bond included sexual access, and also lifelong loyalty and entitlement to social, religious, and political power.

Here is a story from 1475-- a gay romance, a war story, and a Buddhist sermon .

There was a priest named Gemmu, from Kyouto. A young man named Hanamatsu from the Nikko shrines, far to the north, made the trek to the capital. There, Gemmu and Hanamatsu met and fell in love.

But Hanamatsu had to return to the north, and Gemmu promised to join him soon. When Gemmu finally set out to visit his lover, he was climbing the mountainous terrain up to Nikko, he lost his way. Just as he despaired, Hanamatsu found him! The two were happily reunited and spent the night “reminiscing” together at Hanamatsu’s temple.

But when Gemmu woke in the morning, Hanamatsu was gone. When Gemmu went to look for him, he was told that Hanamatsu died only 17 days before.

What had happened was this. Hanamatsu’s father had died in battle. Hanamatsu set out to avenge his father and killed his father’s killer. Then, the surviving son of the killer, killed Hanamatsu in turn.

Gemmu was devastated and awed-- he had been led to safety by Hanamatsu’s spirit. He committed himself to a life of Buddhist devotion.

One year later, he met another young priest dressed in mourning clothes. The young priest explained that his father had been killed, and that he had then killed his father’s killer. But to his shock, he realized that the killer had been a young man his own age, and so turned to Buddhism. This young priest was actually Hanamatsu’s killer.

The young priest and Gemmu spent the rest of their days together in religious devotion, reciting the sutras.

The boy Hanamatsu was actually a bodhisattva, who lived on earth to lead others to the Buddha. Through his love and death, he led two priests to enlightenment.

(paraphrased from Childs 1980)

In this story, there is not only complete acceptance of the same-sex relationship as an erotic and emotional bond, but also as a vehicle for religious transformation.

On a more worldly note, here is a 16th century letter from a Samurai to his boyfriend. By this time, nanshoku was associated with violence and hypermasculinity. After all, what could be more masculine than men loving men?

Now that this situation has come about I feel no particular sorrow. Tonight, I shall fight to the finish at a mountain temple.

In view of our years of intimacy, I am deeply hurt that you should hesitate to die with me. Lest it prove to be a barrier to my salvation in the next life, I decided to include in this final testament all of the grudges against you that have accumulated in me since we first met.

First: I made my way at night to your distant residence a total of 327 times over the past three years. Not once did I fail to encounter trouble of some kind. To avoid detection by patrols making their nightly rounds [after curfew], I disguised myself as a servant and hid my face behind my sleeve, or hobbled along with a cane and lantern dressed like a priest. No one knows the lengths I went to in order to meet you!

Next: Last spring, I casually wrote the poem "My sleeves rot, soaked with tears of jealous rage, [and with them, alas! rots my good reputation, ruined for the sake of love]" on the back of a fan painted by Kano no Uneme in the pattern of a "riot of flowers." You took it and said, "The cool breeze from this fan will help me bear the flames of our love this summer." How happy you made me! But shortly it came to my attention that you gave the fan to your attendant Kichisuke with a note across the poem that said, "This calligraphy is terrible."

Again, when I asked you for your favorite lark as a gift (the one you got from the birdcatcher Jobei), you refused and gave it to Kitamura Shohachi instead. He is, of course, the most handsome boy in the household. My jealousy has not abated yet.

Next: Since the time when we first became lovers, you never once saw me to my house when we bid each other farewell in the morning. In fact, in all these years, you only twice saw me as far a the bridge in front of Uneme's. If you love someone, you should be willing to see him safely home through wilds filled with wolves and tigers.

Though I hold this and that grudge against you, the fact that I cannot bring myself to stop loving you must be the work of some strange fate. To weep is my only comfort. For the sake of our friendship up to now, I ask you to pray, even if but once, for my rebirth in paradise. How strange to think that the impermanence of this world should also affect me.

[He closed the letter with a poem:]

"While yet in full bloom,

it is buffeted by an unexpected gale;

the morning glory

falls with the dew,

ere evening draws nigh."

These are the thoughts I wanted to leave with you. Evening, my last, is drawing nigh, so I shall bid farewell.

WHERE MY LADIES AT??

So in China, Italy, Spain, The Ottoman, Japan-- we’ve seen male-male love as courtly romance, sodomy reviled as a sin, the male form worshipped as the platonic ideal. Also, as the key to power through powerful lovers, and a pathway to Christ’s divinity as well as Buddha’s release, and as an elevation of martial masculinity.

So the elephant who most prominently isn’t in the room? Women. For every mention of female homosexuality or gender non-conformity, there are a hundred male in the historical record.

Most historical references to women’s sexuality are actually about men. Men don’t want their women to be defiled. And men don’t want to be feminized, made into women themselves. This is all misogyny.

Our phallic fallacy basically made lesbian sex into a mystery wrapped in an enigma. In binary societies where the two sexes are the penetrator and the penetratee, there is no sex without a phallus, right?? Thus, lesbian sex is impossible and thereby officially nonexistent.

(Note: This is a late but possibly relevant anecdote: A Scottish judge in 1811 succinctly summarized the accepted view on Lesbians. They are "equally imaginary with witchcraft, sorcery or carnal copulation with the devil.”)

Enough about what men think. Let’s hear from a female Renaissance queer, whose story was scandalous and entertaining enough to make it into the historical canon.

Cross-dressing Conquistador

Cataline De Erauso was a cross-dressing escaped Basque nun born in 1580, who donned men’s clothing and swashbuckled her way to the new world, seducing ladies, gambling and drinking, conquistadoring natives (yikes) swindling and brawling and fighting across Peru. She confessed to being a female only when the sheriffs were closing in (one too many rivals slashed across the face in back-ally rumbles). Her female sex revealed, she was sent to a nunnery. According to her bombastic autobiography, it was like a red-carpet event, the ladies swooning as she went past. She returned to Spain as the celebrity “Lieutenant Nun,” to petition the king for her wages, which he granted.

Then she brawled her way to Rome to see the Pope. Here’s her own account of typical encounter:

I sat down on a stone bench. While there, a well-dressed and gallant soldier came along and also sat down. He had a fine head of hair, and by his accent I knew he was Italian. We greeted each other and began a conversation. He said to me, “You are a Spaniard.” I answered that I was and he responded, “Accordingly you must be overbearing because Spaniards are, and arrogant too, although they are not equal to their boasts.”

I said, “I see them all as pretty well what they say they are.”

He said, “I see them all pretty well as turds.”

Getting up, I said, “Don’t speak that way, for the sorriest Spaniard is better than the best Italian.”

He said, “Will you back up what you say?”

I said, “Yes, I will.”

“Right now, then,” he answered.

“So be it,” said I, and together we went out behind some nearby water tanks. We drew our swords and began to fight, when I saw someone else take his side. They were both slashing but I jabbed, struck the Italian, and dropped him. The other remained, and I was driving him back when another lame but testy fellow (who must have been his friend) came along, took his side, and pressed me. Another fellow came up and took my side, perhaps because he saw I was alone. So many others then joined in that the whole thing became rather confusing. Fortunately I withdrew without anyone noticing, went back to my ship, and knew no more of the matter.

Then she went to visit Pope Urban VIII to tell him her story. She says, “His Holiness showed himself to be astonished by such a tale, and kindly granted me permission to continue my life dressed as a man, charging me to live honestly henceforth and to abstain from offending my neighbor, attaching the threat of the wrath of God to his order, “Non Occides.” [“Do not kill.”]”

The pope’s parting wisdom to De Erauso was not, “stop living as a man,” it was “Stop the senseless violence you absolute gibbon!”

If this swashbuckling memoir is accurate, with a great store of personal charisma, De Erauso gained money and fame through violating the expectations of gender and sex.

A modern interjection! Was this person transgender????

It’s an impossible question. We cannot pose the question to the person directly. We are in a para-social relationship with the past. Transgender is a category that De Erauso would not have immediately understood. The exercise of the imagination is a mirror for us and irrelevant to De Erauso. Maybe he would have heard the term and loved it, saying, “Ha yes, that’s me! Of course I am a man!” Or maybe she would have heard the term and found it baffling-- “No of course not. To live my life in this way, I am an extraordinary female!”

Or maybe, given the option, De Erauso would have said, “none of the above, and none of your business!” and stabbed us behind the water tanks for our trouble.

Genders between the binary and beyond

What about 16th century societies that had gender categories for people who were not men or women? Across the Pacific, Asia, Africa and the Americas, there are societies that have lexical space for genders beyond the man/woman binary. Many of these cultures have been colonized and their story overwritten with Western interpretations. Here I want to be very careful: these “third-gender” groups have been over-referenced by Western LGBT+ people to justify our agendas around sexuality. These genders are distinct from each other and distinct from LGBT+ identities as understood in, for example, the US among over-educated white Queers! In our enthusiasm to discover a global queer experience, we risk oversimplifying the Native meanings and erasing indigenous self-definition.

Here I will rely on the complex machinery of story to carry shared humanity and authentic indigenous meanings.

HAWAII: Loyalty to Partner; fulfill your role as culture keeper

In Hawaii, there are two words to introduce here: Mahu-- people in the middle between male and female, who have special cultural responsibilities, and Aikane-- the role of same-sex romantic partner to a chief. And here, for the first time in our survey, we have a 15th century queer identity category that includes women! Aikane pairs can be male/male, or female/female.

This is a mo’olelo retold by Mahu activist Kumu Hina Wong:

Long before the reign of King Kakuhihewa in the 1500s, four Tahitian healers traveled to Hawaii from their home Moa-ula-nui-akea on the island of Raiatea. Their names were Kapaemahu, who was the leader of the group, Kapuni, Kinohi and Kahaloa. They settled in Waikiki in a place called Ulukou.

The healers were mahu – extraordinary individuals of dual male and female mind, heart and spirit. They were beloved by the people for their gentle ways, and their fame spread as they traveled throughout the islands administering their miraculous cures.

When it was time to depart, they asked that two stones be placed at their residence and two at their bathing place in the sea as a permanent reminder of the relief of pain and suffering from their ministrations. Four huge stones were quarried from the vicinity of the bell rock in Kaimuki, and transported to Waikiki on the night of Kane.

The healers transferred their names and spiritual power to the stones, placing mahu idols under each one. Tradition states that the incantations, fasting and prayers lasted a full cycle of the moon. Then the healers vanished and were seen no more.

The kapaemahu stones are still there today, a reminder of the legacy and of the responsibility modern day mahu carry for their people. Mahu remain the ones who keep the genealogical chants, the hula, and the ceremonies alive. The social power of mahu comes from their service to others. Being Mahu is not gender-transgressive. Transgressing gender expectations for a mahu person means neglecting their responsibilities to their culture.

In the great Hawaiian epic, Ka Huaka’i o Hi’iakaikapoliopele, aikane men and women have adventures that entangle even the gods.

This story takes place after Tahitian settlement on the islands and before the Chief Manokalipo, so between the 1300s and the 1600s. On the island of Hawai’i, Pele, the goddess of the Volcano, dreamed of a handsome man far away on the island of Kauai. He was Lohiau, and she dreamed of him singing with his aikane-- the man Paoa. One look and she fell in love with Lohiau, and HAD to have him. Pele is the Goddess of lava. She gets what she wants. She told her sister Hi’iakaikapoliopele that she had fallen in love. Her sister agreed to go get him for her, as long as Pele promised to take care of Hiiaka’s aikane the woman Hopoe, while she was gone.

Pele promised that Hopoe would come to no harm as long as Hi’iaka brought Lohiau back to her within 40 days.

It’s a long journey from one side of the Hawaiian archipelago (ar-kipela-go) to the other-- there were enemies and monsters and storms, and Hi’iaka faced the obstacles bravely. But when Hi’iaka arrived on Kauai, Lohiau was dead. His partner Paoa was deep in grief. But no problem, a’ole pilikia, Hi’iaka was a goddess-- she brought Lohiau back to life!

Hi’iaka dragged the resurrected man away from his aikane and back to Pele, but arrived too late. In impatient fury, Pele had killed Hi’iaka’s aikane, Hopoe. In grief and despair, Hi’iaka kissed Lohiau, right in front of Pele’s LAVA PIT. Pele erupted and burned them. Hiiaka, being a goddess, got better. Lohiau, however, was dead. Again.

Far away across the islands, Paoa felt Lohiau’s death and came to collect his lover’s body from the volcano. His grief was such that the gods Kane and Ku interfered-- they restored Lohiau again to life.

The bonds between these two aikane same-sex pairs, Hopoe and Hi’iaka; Paoa and Lohiau, were strong enough to invite the wrath, jealousy, and intervention of the gods.

Hawaii is unique among Indigenous nations in that it was an oral culture that embraced the technology of the printed word early and with great enthusiasm. Under the Hawaiian monarchy, Hawaii had the highest literacy rate in the world among all strata of society! (Laimana 2011) Hawaiians wrote down their myths, stories, accounts, and customs in their own language, for themselves very early on, while their nation was still independent. These writings show us the pre-contact Hawaiian experience of gender and sexuality from a Hawaiian point of view.

It is critical to listen to people’s own stories of themselves.

INTERSECTIONALITY

When it comes to the history of sexuality PLUS marginalized people such as women, racial or religious minorities, and the poor-- it’s tricky. Most of the time those folks were not the ones keeping the records. The overlap of identities means that queerness will impact people differently depending on their social status.

Wealthy, highly educated, religious-majority, and well-connected young men will continue to get away with things that say, a religious-minority woman, a displaced Native, or an enslaved boy, could not.

Discrimination and prejudice will fall harder on people who already lack power.

When we have no record of their interiorities, their poetries and songs and liturgies and flirtations, and only criminal records or tabloids or dusty archeology, it is fair to mourn the loss of those voices, to hear the emptiness where those words could have been.

First Nations

For American first nations, the 15th and 16th centuries were the apocalypse, the alien invasion. They experienced cultural genocide. So much was lost-- languages and cultures and lives. The survivors and their descendants have worked hard to safeguard their cultures. Although we lack written first person accounts of queer people from that time, through linguistics, oral history, art, and ceremony we know that the Maya, Hopi, Cheyenne, Lakota, Zuni, Navajo, Aztec and others have had names for third gender people with specific social and supernatural roles beyond the binary for hundreds of years, stretching back before colonization to the origins of Turtle Island.

16th century genocidal Europeans encountering Native people clutched their pearls about the rampant sexual vice and debauchery they saw. Later anthropologists made more sympathetic but equally biased accounts of Native American sexuality and gender, conflating Indian third genders with European male prostitution, since they couldn’t imagine a different gender construct to explain what they saw than berdache.

The English-language term “Two-Spirit” was coined in 1990 and has been adopted as a pan-Indian term for people who are called to live and work beyond the worlds of male and female, natural and supernatural.

The Reverend Isaiah Brokenleg explains his identities: (Drager 2021) “For a lot of non-Indian LGBTQ individuals, ‘coming out’ is an independent identity. But when you’re coming out as two-spirited, it’s much more of a coming in. We often come into the sense of belonging. We come into our understanding of the two-spirited identity and what our role and place is within our communities and family. It’s not a declaration. It’s a presentation to our communities that we are ready to serve. Within my culture, I can be Indian, gay and winkte. I don’t have to leave a part of myself behind.”

Battle of the Hundred-in-the-Hands."

In the pre-contact past, Lakota tribe Winkte had specific responsibilities in war, as they are able to bridge the present and the future, the enemy and the ally, fighting and healing. Gimmel, an early conservationist, writes, “When a war-party was preparing to start out, one of these persons was often asked to accompany it, and, in fact, in old times large war-parties rarely started without one or two of them. They were good company and fine talkers. When they went with war-parties they were well treated. They watched all that was being done, and in the fighting cared for the wounded, in which they were skillful, for they were doctors or medicine men.” (Zimmy 2016 quoting Gimmel )

The Oglala chief American Horse (b 1840) created this Winter-count record called The Winkte and the Hundred in Hand. It is a depiction of a pivotal battle in the Plains Indians’ war against the American settlers. A Lakota Winkte under Chief Red Cloud saw visions of victory against the American soldiers and set out to make an alliance with enemy tribes.

Grinnel writes, “Soon a person, half man and half woman – winkte – with a black cloth over his head, riding a sorrel horse, pushed out from among the Sioux and passed over a hill, zigzagging one way and another as he went. He had a whistle, and as he rode off he kept sounding it.While he was riding over the hill some of the Cheyennes were told by the Sioux that he was looking for the enemy – soldiers.

On the fourth return he rode up fast, and as his horse stopped he fell off and both hands struck the ground. “Answer me quickly,” he said, “I have a hundred or more,” and when the Sioux and Cheyennes heard this they all yelled.

This was what they wanted. While he was on the ground some men struck the ground near his hands, counting the coup. (Grinnel, p. 228-229)

The tribes united against a common enemy, because the Winkte had shown the way to bridge the distance between them.

In mythology, between-gender or two-gender gods like the Lakota morning God Anpao keep the world in balance. Winkte people explain that this is their role: to be a go-between.

The sketch “Employments of the Hermaphrodites”, made in Florida in the 1560s shows two between-gender people carrying bodies on a stretcher. It confirms what modern two-spirit people say: they are the caretakers, able to move in liminal spaces that male or female people can not.

One Lakota winkte person interviewed in 1982 said, “Winkte are wakan, which means that they have power as special people. Medicine men go to winkte for spiritual advice. Winktes can also be medicine men, but they’re usually not because they already have the power….I want to be remembered most for the two values that my people hold dearest: generosity and spirituality. If you say anything about me, say those two things.” (Williams, p. 198-199).

(Note: “Formerly, higher class winktes had up to twelve husbands. Chief Crazy Horse had one or two winktes for wives, as well as his female wives, but this has been kept quiet because Indians don’t want whites to criticize” (Newberg 2022). “I love children, and I used to worry that I would be alone without children. The Spirit said he would provide some. Later, some kids of drunks who did not care for them, were brought to me by neighbors. The kids began spending more and more time here, so finally the parents asked me to adopt them. In all, I have raised seven orphan children.” “I worked as a nurse, and a cook in an old age home. I cook for funerals and wakes too. People bring their children to me for special winkte names, and give me gifts.” (Newberg 2022: These auspicious names were often bawdy and humorous, but of such spiritual power that they ought not be spoken out loud for fear of losing their power. Sitting Bull, Black Elk, and Crazy Horse are all said to have received such names (Lang, p. 180-181).) He continues: “If I show my generosity, then others help me in return. Once I asked the spirit if my living with a man and loving him was bad. The spirit answered that it was not bad because I had a right to release my feelings and express love for another, that I was good because I was generous and provided a good home for my children.")

Gender is a matrix of relationships, responsibilities to individuals and communities, class, power, sex, spiritual identity, reproduction, anatomy, and mythology. It can be binary based on either reproductive or sexual behavior. Or it can be a set of social roles that allow for third genders to bring balance to a divided world.

New (queer??) lines of approach: Folklore, meaning-making, history, fandom studies

How do we braid together these queer story strands of sexuality, interiority, and power with the LGBT+ present?

If we’re being taxonomists, looking for evidence of modern-matched queer typologies in the past, we may spot what appears to be a typological homosexual phenotype from 500 years ago and then realize that, actually no. Behavior doesn’t signify what we think it does.

We can spot queer things in the past, but the sense we make of them, without context, is subjective, personal and unscientific.

Ah well, let’s put aside our physics envy. The taxonomical urge to claim cultural cognates has a history of harm. In the intricate realm of stories of human intimacy and gender identity, we need curiosity, not catalog.

We can hear queer voices of the past the way we interact with literature: with mirrors and pitch-forks and tuning forks and a dictionary. With a beginner’s-- a fan’s mind.

Where historical literary criticism often works for authoritative interpretation and tries to disguise the desires of the critic, fan engagement is creative and openly subjective.

Historians can learn from fan-creators. We can look closely at historical canon, acknowledge what WAS, what IS, and then deploy our creativity and imagination to empathize.

So what can we take with us from the past into the future?

The stories we’ve heard tell the inner experience of queerness in relation to society. Religion, money, power, war, lust, service, responsibility-- queer stories are warped in bright threads through the weft of their contexts. So can we-- should we-- learn anything from the queer past? Is it too alien to be relevant?

(Note: Hinsch, 3 “Why should a modern Westerner be interested in understanding the sexual practices of a people far removed in both time and place? In Western-centric terms, this sort of investigation allows us to comprehend the sexual practices of our own culture by providing an alternate, sophisticated panorama of sexual behavior….By carefully examining the sexuality of a people divided from us by time and place, we can better understand and question the caprice implicit in our own social and sexual conventions.”)

Humility: societies really are different. Europe had a horror of anality; Japan had a fascination with it. Some religions, like Christianity, reviled homosexuality, some embraced it like Japanese Buddhism, some ignored it like Confucianism. Some cultures believed that everyone was potentially bisexual, some believed that homosexuality is a rare mutation. Some believed that gender is based on power-- who penetrates whom, and who gets penetrated! Some believed that gender is based on who you serve, what you build, who you care for.

If such fundamental views can be different, maybe there aren’t absolute truths about the stories we tell ourselves about our genders, sexualities, and obligations to each other.

Looking at the diversities of the queer past expands the kinds of intimate bonds we can imagine having, both “straight” and “queer.” And we could use that expansion. Queer people need safety from violence. And straight people need help, marriage.

There can be a diversity of intimacies that today all fall under the narrow bounds of romance: infatuation, love, lust, duty, friendship, mentorship, loyalty, worship, partnership-- those can be housed in different relationships rather than heaped all at the feet of one poor unsuspecting spouse, of the same or different sex.

As history fans we can have empathy. The same confessional drive that caused these folks to write sappy love poetry to their favorite people, to send ill-advised letters to boys out of their league, to be considerate of their lovers at one point and feel disgust for them later, to brag about their conquests, to care for their people-- we can relate to the essential humanity in those storytelling acts, without the hubris of assuming their ways are our ways, or our values are their values. We can relate AND differentiate.

Conclusion

How we define “normal” vs. “queer” will continue to evolve. Sexuality and gender performance will give access to some kinds of power and curtail others as history arcs on. We can take a broad view and see that the constant of human sexuality is its variety. Here at last I make brief mention of our patroness Dorothy Dunnett!

Lymond!“That Queer Dilettante Sect”

She was an insightful fan/historian of the past, and surgically observant of human interiority. The Lymond Chronicles are not considered a queer text but Francis Crawford navigates queer diversities in the 16th century, and capitalizes on homosocial and homosexual bonds. Dunnett allowed Lymond (and her other characters) to be more than the limits of their genders, their sexual behaviors, and their times. Lymond’s 16th century interpersonal universe is complex, and the identity possibilities are open, freed from the taxonomical burden of identity essentialism. Self-determination and autonomy is the ideal, as individuals and as nations.

We can, with this understanding of diversity, hear each other’s stories.

We can oppose forces that punish marginalized people for what they are OR what they do. We can allow ourselves and others self-definition, and with the gentleness of the cut-sleeve, let sleeping lovers lie.

Sources

Alpert, R. R. T. (2017, February 25). History of Jewish lesbianism. My Jewish Learning. Retrieved March 26, 2023, from https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/history-of-jewish-lesbianism/

Adams, L. (2022, July 20). The "middle" gender in zuni religion. Owlcation. Retrieved March 26, 2023, from https://owlcation.com/social-sciences/

Andrews, W. G., & Kalpaklı, M. (2006). The age of beloveds: Love and the beloved in early-modern Ottoman and European culture and Society. Duke Univ. Press.

Boswell, J. (1995). Same-sex unions in Premodern Europe. Vintage Books.

Boswell, J. (2015). Christianity, social tolerance, and homosexuality: Gay people in Western Europe from the beginning of the Christian era to the fourteenth century. The University of Chicago Press.

Bray, A. (1994). Homosexuality and the Signs of Male Friendship in Elizabethan England. In J. GOLDBERG (Ed.), Queering the Renaissance (pp. 40–61). Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv123x7cr.5

Brown, J. C. (1988). Immodest acts: The life of a lesbian nun in Renaissance Italy. Oxford University Press.

Carpenter, E. (1902). Ioläus: An anthology of friendship. London : Allen & Unwin.

Childs, M. H. (1980). Chigo Monogatari. Love Stories or Buddhist Sermons? Monumenta Nipponica, 35(2), 127–151. https://doi.org/10.2307/2384336

Crompton, L. (2006). Homosexuality & civilization. The Belknap Press of Harvard University.

de Ferrer, J. M., & de Erauso, C. (1881). Historia de la Monja Alférez, Doña Catalina de Erauso. (D. H. Pedrick, Trans.). Impr. de Diego Pachecho y Cia. Retrieved March 26, 2023, from http://eada.lib.umd.edu/text-entries/the-autobiography-of-dona-catalina-de-erauso/

Dundes, A. (2002). Much Ado about “Sweet Bugger All”: Getting to the Bottom of a Puzzle in British Folk Speech. Folklore, 113(1), 35–49. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1261005

Dunne, B. W. (1990). Homosexuality in the Middle East: An Agenda for Historical Research. Arab Studies Quarterly, 12(3/4), 55–82. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41857885

Fraiman, J. (2018, January 5). James M. Saslow on sensuality and spirituality in Michelangelo's poetry. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved March 19, 2023, from https://www.metmuseum.org/blogs/now-at-the-met/2018/james-saslow-interview-michelangelo-poetry

Gemmell, J. (2020, September 27). Homosexuality in Renaissance Florence: The ambiguities of Neoplatonic thought. Retrospect Journal. Retrieved March 19, 2023, from https://retrospectjournal.com/2019/11/10/homosexuality-in-renaissance-florence-the-ambiguities-of-neoplatonic-thought/

Halperin, D. M. (1989). Is There a History of Sexuality? History and Theory, 28(3), 257–274. https://doi.org/10.2307/2505179

Halperin, D.M. (2000). How to Do the History of Male Homosexuality. GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 6(1), 87-123. https://www.muse.jhu.edu/article/12121.

Halperin, D. M. (2002) How to do the history of homosexuality. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press..

Herrada, G. (2013). The missing myth a new vision of same-sex love. SelectBooks.

Hinsch, B. (1992). Passions of the cut sleeve the male homosexual tradition in China. University of California Press.

Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., Baker, M., Harris, T., & Stephenson, D. (2015). Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(2), 227–237. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691614568352

Holt-Lunstad, J. (2021). Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors: The power of Social Connection in Prevention. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, 15(5), 567–573. https://doi.org/10.1177/15598276211009454

Hooker, R. (1996). Michelangelo Selected Poetry. Course: Philosophy . Retrieved April 8, 2023, from http://www.faculty.umb.edu/gary_zabel/Website/index.html

ho'omanawanui, ku'ualoha. (2014). Voices of fire: Reweaving the literary lei of Pele and hi'iaka. University of Minnesota Press.

Jenkins, H. D. (1911). Ibrahim Pasha: Grand Vizir of Suleiman the Magnificent. Nabu Press.

Johnson, T. (2000). Saint John of the Cross and the Dark Night. Saint John of the Cross' Dark Night and Gay Consciousness. Retrieved April 8, 2023, from https://www.tobyjohnson.com/darknight.html

King, R. (2014). Leonardo and the last supper. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Leupp, G. P. (1995). Male colors: The construction of homosexuality in tokugawa Japan. Univ. of Calif. Press.

Murray, S. O. (1994). On Subordinating Native American Cosmologies to the Empire of Gender. Current Anthropology, 35(1), 59–61. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2744140

Murray, S. O. (1997). Explaining Away Same-Sex Sexualities: When They Obtrude on Anthropologists’ Notice at All. Anthropology Today, 13(3), 2–5. https://doi.org/10.2307/2783130

Murray, S. O. (2002). Pacific homosexualities. Writers Club Press.

Murray, S. O. (2007). Homosexuality in the Ottoman Empire. Historical Reflections / Réflexions Historiques, 33(1), 101–116. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41299403

Newberg, B. T. (2022, September 20). Two-spirit: The Lakota winkte – sex on the Great Plains. The History of Sex. Retrieved March 19, 2023, from https://historyofsexpod.com/2022/10/03/two-spirit-the-lakota-winkte-sex-on-the-great-plains/

Norton, R. (2016). Myth of the Modern Homosexual: Queer History and the Search for Cultural Unity. United Kingdom: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Nye J (2017) Soft power: the origins and political progress of a concept. Palgrave Communications. 3:17008 doi: 10.1057/palcomms.2017.8.

O'Brien, J. A., & de Vries, K. M. (2009). Berdache (Two-Spirit). In Encyclopedia of gender and society (p. 64). essay, Sage.

Poudel-Tandukar, K., Nanri, A., Mizoue, T., Matsushita, Y., Takahashi, Y., Noda, M., Inoue, M., & Tsugane, S. (2011). Social support and suicide in Japanese men and women – The Japan Public Health Center (jphc)-based prospective study. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 45(12), 1545–1550. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.07.009

Pu, S., Giles, H. A., & Cass, V. B. (2017). Strange tales from a Chinese studio: Eerie and Fantastic Chinese stories of the supernatural. Tuttle Publishing.

Robb, G. (2005). Strangers homosexual love in the Nineteenth Century. W.W. Norton & Company.

Rocke, M. (2010). Forbidden friendships: Homosexuality and male culture in Renaissance Florence. Oxford Univ. Press.

Rūmī Jalāl al-Dīn, Ergin, N. O., & Johnson, W. (2006). The forbidden rumi: The suppressed poems of Rumi on love, heresy, and intoxication. Inner Traditions.

Schick, İ. C. (2021, April 8). What ottoman erotica teaches us about sexual pluralism. Aeon. Retrieved March 19, 2023, from https://aeon.co/ideas/what-ottoman-erotica-teaches-us-about-sexual-pluralism

Shamgunova, N. (2022, December 13). Missing voices in the age of the beloveds: Ottoman same sex intimacy. History Workshop. Retrieved March 26, 2023, from https://www.historyworkshop.org.uk/sexuality/missing-voices-in-the-age-of-the-beloveds-ottoman-same-sex-intimacy/

Sienna, N., & Plaskow, J. (2020). A rainbow thread: An anthology of queer jewish texts from the First Century to 1969. Print-O-Craft Press.

Tedlock, B. (1984). The Beautiful and the Dangerous Zuni Ritual and Cosmology as an Aesthetic System. Conjunctions, 6, 246–265. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24515110

Temming, M. (2023, March 7). Why fandom feels good - and may be good for you. Science News Explores. Retrieved April 8, 2023, from https://www.snexplores.org/article/fandom-fan-psychology-comiccon-marvel-fiction

Wilhelm, J. J. (1995). Gay and lesbian poetry: An anthology from Sappho to Michelangelo. Garland.

Xian, K., Anbe, B., Carvajal, J., Florez, C. M., & Reichel, K. (2001). Ke kulana he māhu : remembering a sense of place : a documentary. Zang Pictures.

Zimmy, M. (2016, June 6). The winkte and the hundred in hand. South Dakota Public Broadcasting. Retrieved March 26, 2023, from https://www.sdpb.org/blogs/arts-and-culture/the-winkte-and-the-hundred-in-hand/

Comments

Post a Comment